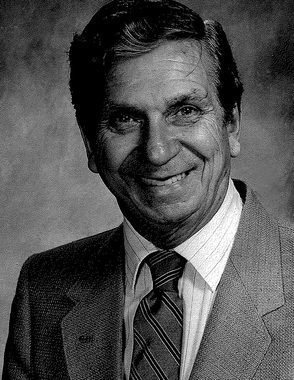

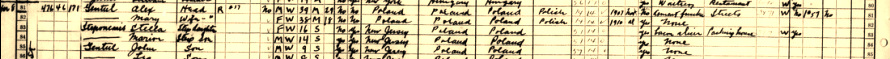

Jack was born on April 18, 1920 at 476 Henderson Street, Newark, New Jersey. His parents, Alex and Mary Gentul, were immigrants from Poland. Alex Gentul worked at a cement foundry making paving materials while Mary took care of Jack and his step-siblings, Stella and Marion. Because Jack's family was poor he was compelled to quit school early to help support them. However, he was naturally brilliant and an avid reader.

Serving in the Army Air Force in WW II, where he attained the rank of corporal, Jack received training in electronics. After the war, he began taking electronics courses at Newark College of Engineering (now part of the New Jersey Institute of Technology). Jack began his career working in the design and repair of television circuits. His family was a beneficiary of that work -- Jack built them a TV that had the largest screen on the block! Jack later migrated to the field of audio amplification. Again, Jack's family were the beneficiaries of his yen for innovation: Jack installed audio speakers and wiring into the walls of his home decades before such installations became common.

His career is challenging to trace. The following represents the currently-verifiable chronology:

Serving in the Army Air Force in WW II, where he attained the rank of corporal, Jack received training in electronics. After the war, he began taking electronics courses at Newark College of Engineering (now part of the New Jersey Institute of Technology). Jack began his career working in the design and repair of television circuits. His family was a beneficiary of that work -- Jack built them a TV that had the largest screen on the block! Jack later migrated to the field of audio amplification. Again, Jack's family were the beneficiaries of his yen for innovation: Jack installed audio speakers and wiring into the walls of his home decades before such installations became common.

His career is challenging to trace. The following represents the currently-verifiable chronology:

Brook Electronics

As of the fall of 1952, Jack was affiliated with Brook Electronics, Inc. 34 DeHart Place, Elizabeth, New Jersey. Brook Electronics was an exhibitor at the 1952 Audio Fair in New York City, describing itself as manufacturing "Brook high-quality audio amplifiers." According to the November, 1952 edition of Audio Engineering Magazine, Brook sent Jack and three other individuals to represent it at the Fair: Lincoln Walsh, who had founded Brook shortly before WW II; Ann F. Hall (about whom nothing else is known), and Frank Hill. Frank Hill is key: he and Jack would go on to start the Hilgen Manufacturing Company.

The Brook Electronics connection may be critical to determining Jack Gentul's vision for the Hilgen line of amplifiers. The folks at Brook Electronics were the heavies in the ultra-hi-fi industry at that time. Jack was inspired by Lincoln Walsh, whom he described as having a "great mind." Most folks would agree. Born in 1903, Mr. Walsh obtained degrees from Brooklyn College, Stevens Institute of Technology, and Columbia University, During WWII he worked with Dr. Rudy Bozak to develop power supplies for radar installations. After the war Lincoln and Rudy collaborated in creating the legendary (and really expensive) Bozak speaker system. In 1964, Mr. Walsh invented a pretty good speaker of his own -- the "Coherent Wave Transmission Line Driver" -- for which he received a patent in 1969. The Walsh driver is still considered one of the finest loudspeakers ever made. Although Mr. Walsh never developed his invention commercially, an enterprising gentleman named Martin Gersten purchased the patent and began producing the legendary (and really expensive) Ohm Acoustics speakers. Mr. Walsh also designed the legendary (and really expensive) Brook "High Quality Audio Amplifier." Make a note of that: it was was a "High Quality Audio Amplifier." If you can find a vintage 30W Brook amplifier these days, it will only set you back about $10,000 -$ 15,000. Paul Klipsch, famous for his "Klipschorn" line of speakers, insisted on using Brook amplifiers to demonstrate his speakers' full capabilities.

Mr. Walsh and Jack remained good friends until Mr. Walsh died in 1971. It is logical to suppose that Jack discussed amplifier designs with Mr. Walsh during Jack's later career. It is also logical to suppose that the older, more experienced man taught his protege a thing or too.

The Brook Electronics connection may be critical to determining Jack Gentul's vision for the Hilgen line of amplifiers. The folks at Brook Electronics were the heavies in the ultra-hi-fi industry at that time. Jack was inspired by Lincoln Walsh, whom he described as having a "great mind." Most folks would agree. Born in 1903, Mr. Walsh obtained degrees from Brooklyn College, Stevens Institute of Technology, and Columbia University, During WWII he worked with Dr. Rudy Bozak to develop power supplies for radar installations. After the war Lincoln and Rudy collaborated in creating the legendary (and really expensive) Bozak speaker system. In 1964, Mr. Walsh invented a pretty good speaker of his own -- the "Coherent Wave Transmission Line Driver" -- for which he received a patent in 1969. The Walsh driver is still considered one of the finest loudspeakers ever made. Although Mr. Walsh never developed his invention commercially, an enterprising gentleman named Martin Gersten purchased the patent and began producing the legendary (and really expensive) Ohm Acoustics speakers. Mr. Walsh also designed the legendary (and really expensive) Brook "High Quality Audio Amplifier." Make a note of that: it was was a "High Quality Audio Amplifier." If you can find a vintage 30W Brook amplifier these days, it will only set you back about $10,000 -$ 15,000. Paul Klipsch, famous for his "Klipschorn" line of speakers, insisted on using Brook amplifiers to demonstrate his speakers' full capabilities.

Mr. Walsh and Jack remained good friends until Mr. Walsh died in 1971. It is logical to suppose that Jack discussed amplifier designs with Mr. Walsh during Jack's later career. It is also logical to suppose that the older, more experienced man taught his protege a thing or too.

Sano manufacturing

Stanley Michael provides the long-conjectured link between the New Jersey amplifier companies Ampeg, Sano, and Hilgen.

According to Ampeg: The Story Behind the Sound, in 1946 Mr. Michael (not "Michaels") entered into a partnership with Everett Hull which was first called "Michael-Hull Electronic Labs." Two or three years later, Mr. Michael left the partnership, after which Mr. Hull changed the name of the company to one of legend: Ampeg (technically, "Ampeg Bassamp Company.") It is oft reported that Mr. Michael designed Ampeg's first amplifier, the "Bassamp."

Sources on the Internet frequently assert that Mr. Michael founded Sano Amps. That is incorrect. Sano was formed in 1951 by three talented individuals: Nick Sano, an accordion player; Joe Zonfrilli, an electronics technician; and Lou Iorio (Mr. Zonfrilli's brother-in-law), who worked primarily as a music teacher. Mr. Michael as essentially an electronics consultant to Sano, not a hands-on participant in the company.

By the way, the "a" in "Sano" is pronounced like the "a" in "cat." Until I spoke with Fred Zonfrilli, I had always pronounced it "ah."

Mr. Michael met Mr. Gentul at some point before 1953. How or when is currently unknown. Fred Zonfrilli recalls Mr. Gentul starting work at Sano in about 1953. It was Stanley Michael who recommended Jack to Sano as a full-time electronics designer. Therefore, Messrs. Michael and Gentul must have become fairly familiar with each other's capabilities before 1953. Because there seems to have been considerable cross-pollination among the pioneers of audio amplification in the late 1940's and early 1950's, the meeting could have happened while Jack was with Brook Electronics, or while Mr. Michael was with Ampeg. Or it could have happened anywhere.

According to Fred Zonfrilli, Mr. Michael invented the very first accordion pickup for Mr. Sano, and also designed the first Sano accordion amp in about 1951. After Mr. Gentul arrived in 1953, he became a full-time employee of Sano. Jack was in charge of design and production of Sano's electronic products.

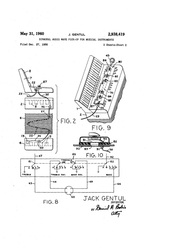

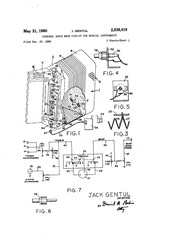

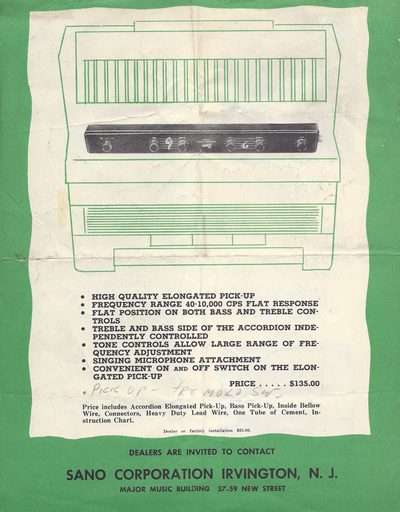

One of Jack's significant early projects for Sano was to design a a "binaural" pickup for the accordion that had separate microphones for the treble and bass reeds, could produce tremolo on either or both frequency ranges, and even incorporated an input for a vocal mike! Jack applied for a patent for his invention in 1956, and was granted the patent in 1960:

According to Ampeg: The Story Behind the Sound, in 1946 Mr. Michael (not "Michaels") entered into a partnership with Everett Hull which was first called "Michael-Hull Electronic Labs." Two or three years later, Mr. Michael left the partnership, after which Mr. Hull changed the name of the company to one of legend: Ampeg (technically, "Ampeg Bassamp Company.") It is oft reported that Mr. Michael designed Ampeg's first amplifier, the "Bassamp."

Sources on the Internet frequently assert that Mr. Michael founded Sano Amps. That is incorrect. Sano was formed in 1951 by three talented individuals: Nick Sano, an accordion player; Joe Zonfrilli, an electronics technician; and Lou Iorio (Mr. Zonfrilli's brother-in-law), who worked primarily as a music teacher. Mr. Michael as essentially an electronics consultant to Sano, not a hands-on participant in the company.

By the way, the "a" in "Sano" is pronounced like the "a" in "cat." Until I spoke with Fred Zonfrilli, I had always pronounced it "ah."

Mr. Michael met Mr. Gentul at some point before 1953. How or when is currently unknown. Fred Zonfrilli recalls Mr. Gentul starting work at Sano in about 1953. It was Stanley Michael who recommended Jack to Sano as a full-time electronics designer. Therefore, Messrs. Michael and Gentul must have become fairly familiar with each other's capabilities before 1953. Because there seems to have been considerable cross-pollination among the pioneers of audio amplification in the late 1940's and early 1950's, the meeting could have happened while Jack was with Brook Electronics, or while Mr. Michael was with Ampeg. Or it could have happened anywhere.

According to Fred Zonfrilli, Mr. Michael invented the very first accordion pickup for Mr. Sano, and also designed the first Sano accordion amp in about 1951. After Mr. Gentul arrived in 1953, he became a full-time employee of Sano. Jack was in charge of design and production of Sano's electronic products.

One of Jack's significant early projects for Sano was to design a a "binaural" pickup for the accordion that had separate microphones for the treble and bass reeds, could produce tremolo on either or both frequency ranges, and even incorporated an input for a vocal mike! Jack applied for a patent for his invention in 1956, and was granted the patent in 1960:

(Clearly, Jack was not the dull boy...)

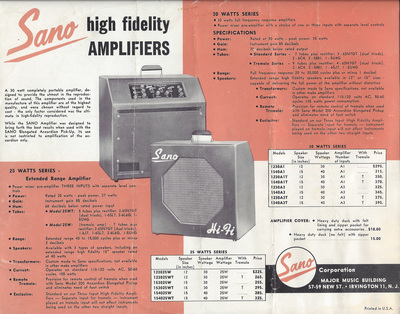

Most importantly for the Hilgen story, Jack designed the circuits for all of Sano's tube amplifiers from about 1953 until about 1964. This, by itself, would be sufficient to render Mr. Gentul of significant importance in the history of guitar amplification. Go on the Internet and see if you can find a review of a pre-'64 Sano amp that does not have overtones of amazement. (This is not to diminish the importance of Joe Zonfrilli, Sr. in the development of Sano amps. He was in charge of the entire enterprise, and was said to have been responsible for the industrial design of the amplifiers so as to make them as attractive and useful as possible. I've much more to learn and write about Joe.)

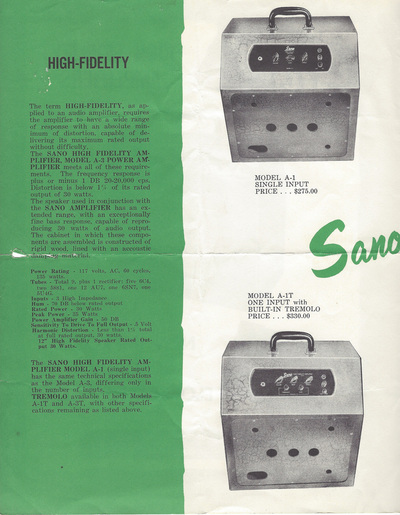

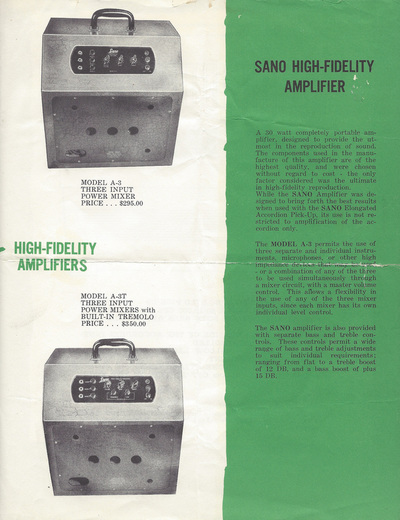

Jack preserved in his personal archives sales literature from his time at Sano (click to enlarge images):

Most importantly for the Hilgen story, Jack designed the circuits for all of Sano's tube amplifiers from about 1953 until about 1964. This, by itself, would be sufficient to render Mr. Gentul of significant importance in the history of guitar amplification. Go on the Internet and see if you can find a review of a pre-'64 Sano amp that does not have overtones of amazement. (This is not to diminish the importance of Joe Zonfrilli, Sr. in the development of Sano amps. He was in charge of the entire enterprise, and was said to have been responsible for the industrial design of the amplifiers so as to make them as attractive and useful as possible. I've much more to learn and write about Joe.)

Jack preserved in his personal archives sales literature from his time at Sano (click to enlarge images):

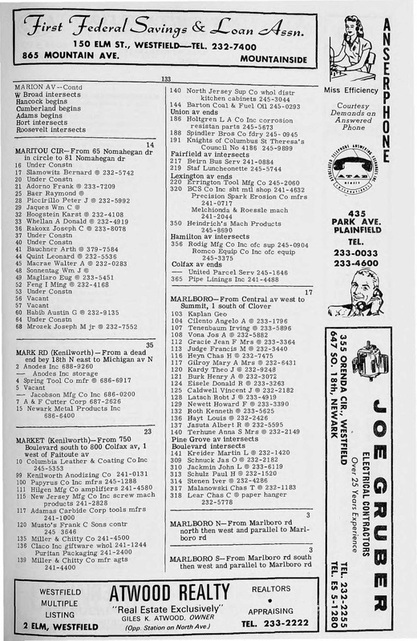

hilgen manufacturing company

The control panels on Sano amplifiers were black, and generally carried the inscription "High Quality Amplifier." That's right. "High Quality."In approximately 1963 or 1964, Mr. Gentul and Frank Hill, his former colleague at Brook Electronics, founded Hilgen Manufacturing Company. The company's name was derived

from the partners' last names: "Hill" + "Gentul" =

"Hilgen." Thus, there is no truth to the oft-repeated assertion

that the name "Hilgen" is related to Hillside, New Jersey.

When he formed Hilgen, Jack was still an employee of the Sano Company. Joe Zonfrilli was understandably uncomfortable with the fact that his amp circuitry designer was becoming a competitor with the company that employed and paid him. Mr. Zonfrilli offered Mr. Gentul a choice between continuing with Sano exclusively or else terminating his relationship with the company. Jack chose the latter, and left Sano in about 1964 to concentrate full-time on Hilgen Manufacturing.

When he formed Hilgen, Jack was still an employee of the Sano Company. Joe Zonfrilli was understandably uncomfortable with the fact that his amp circuitry designer was becoming a competitor with the company that employed and paid him. Mr. Zonfrilli offered Mr. Gentul a choice between continuing with Sano exclusively or else terminating his relationship with the company. Jack chose the latter, and left Sano in about 1964 to concentrate full-time on Hilgen Manufacturing.

Jack first operated Hilgen in the basement of his father's home at 507 McMichael Place, Hillside, New Jersey.

(recent photograph by Miriam Bein)

(recent photograph by Miriam Bein)

By the end of 1964, Hilgen moved to a manufacturing facility at 111 Market Street, Kenilworth, New Jersey.

(now, according to Google Maps, the proud home of Metro Auto

Electronics)

(now, according to Google Maps, the proud home of Metro Auto

Electronics)

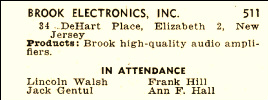

1965 Cranford New Jersey Directory

Just imagine that it's 1965, and you're looking up Hilgen Manufacturing in the phone book. You know they're somewhere on Market Street...

And you can bet that if you dialed Hilgen's number, someone would pick up promptly. Who, after all, would dare disagree with Miss Efficiency's admonition at the top right corner of the page: "Courtesy Demands An Answered Phone."

The Hilgen Mfg. Co. maintained a listing at the 111 Market Street address in the 1964, 1965, and 1966

Cranford directories.

And you can bet that if you dialed Hilgen's number, someone would pick up promptly. Who, after all, would dare disagree with Miss Efficiency's admonition at the top right corner of the page: "Courtesy Demands An Answered Phone."

The Hilgen Mfg. Co. maintained a listing at the 111 Market Street address in the 1964, 1965, and 1966

Cranford directories.

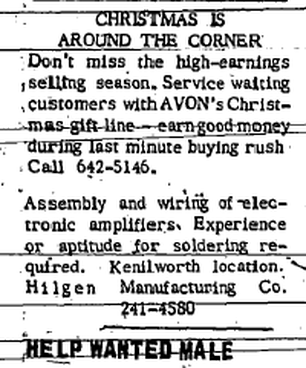

If you needed a little extra money around the holidays, you had a choice: selling Avon cosmetics, or building guitar amplifiers at Hilgen's Kenilworth facility.

. It is unclear whether Jack actually built any

Hilgen-branded amplifiers in 1964. Thus far I have found no amps branded

"Hilgen" dated before 1965.

Frank Hill severed his ties with Hilgen after a few years at most. I have no information about the circumstances of his departure.

Frank Hill severed his ties with Hilgen after a few years at most. I have no information about the circumstances of his departure.

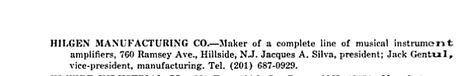

The publication "Music Trades" printed this description in its 1964, 1965, and 1965 editions. Evidently the amplifiers were manufactured at Kenilworth, but the company maintained a business office at Hillside.

As the advertisement confirms, after Frank Hill departed, Jacques "Jack" Silva entered into a partnership agreement with Jack to run Hilgen. Mr. Silva had for many years been the President of Radio-Matic Corporation of America, a company that began by distributing coin-operated radios built by GE and later became a major supplier of electronics parts. Sano had been a customer of Radio-Matic, which is probably how Mr. Gentul and Mr. Silva met. Radio-Matic was apparently the source for the parts and cabinets for the Hilgen amplifiers. Mr. Silva provided capital for Hilgen and was also in charge of the marketing and distribution of the amps.

Jack was not interested in running a business. He wanted to design and build amps. Hence it was agreed that Mr. Silva would be designated the "president" of Hilgen and earn a percentage of the profits, while Jack would hold the title of "vice-president, manufacturing" and be paid a salary. It was further agreed that, in return for his investment, Mr. Silva would hold a controlling 51% interest in the partnership. As later events proved, this was not necessarily the best decision Jack ever made.

As the advertisement confirms, after Frank Hill departed, Jacques "Jack" Silva entered into a partnership agreement with Jack to run Hilgen. Mr. Silva had for many years been the President of Radio-Matic Corporation of America, a company that began by distributing coin-operated radios built by GE and later became a major supplier of electronics parts. Sano had been a customer of Radio-Matic, which is probably how Mr. Gentul and Mr. Silva met. Radio-Matic was apparently the source for the parts and cabinets for the Hilgen amplifiers. Mr. Silva provided capital for Hilgen and was also in charge of the marketing and distribution of the amps.

Jack was not interested in running a business. He wanted to design and build amps. Hence it was agreed that Mr. Silva would be designated the "president" of Hilgen and earn a percentage of the profits, while Jack would hold the title of "vice-president, manufacturing" and be paid a salary. It was further agreed that, in return for his investment, Mr. Silva would hold a controlling 51% interest in the partnership. As later events proved, this was not necessarily the best decision Jack ever made.

Like many men of his generation, Jack was highly focused on his job, usually working six days a week. However, he was no fanatic; Jack was one to take the back roads and, to coin a phrase, "stop and smell the roses." His marriage and his children were important to him. On Saturdays he'd bring his son to work with him, allowing him to see first-hand the esoteric things Dad did for a living, sometimes meeting luminaries in the music industry in the process.

Hilgen's first amplifier was the "HM-B." Not much of a name. Perhaps that's why "HM-B" only appears in tiny little letters on the right side of the control panel. In the middle, where the model name would ordinarily appear, are printed the words "High Quality Amplifier." Hmmm. Where have we heard that before? There was no indication whether it was a guitar amp, a bass amp, or an accordion amp, although it had separately labelled inputs for each of them. The schematic for the HM-B (the only Hilgen schematic known to exist) describes it as a bass amplifier. But all the consumer evidently needed to know was that it was a "High Quality" amplifier -- just like Brook, and just like Sano.

Mr. Silva recalls that Jack continued the Sano tradition of attempting to make Hilgen amplifiers suitable for accordion. Mr. Silva unsuccessfully urged Jack to develop an amplifier specifically designed to amplify the electric violin. I thought that a rather odd statement until I discovered that Fender had made an electric violin in 1958-1959 and that both Rickenbacker and National had produced electric violins in the 1930's and 40's. Where would be now if Hendrix had picked up the electric violin?

Hilgen remained a going concern from 1964 until some time in 1967. There are no records of how many amplifiers the company built or shipped. (Indeed, there is literally no documentary evidence of what went on at Hilgen -- including, most regrettably, schematics for any amplifier other than the early HM-B.) Jack often invited musicians to try out his new amp designs and provide feedback on how they could be improved before they were put into general production.

One of the most telling descriptions I have heard of Jack is the following: "He was not so much an audiophile but fascinated with what he could do with sound." At first I was taken aback my that observation; because of his early involvement with the upscale Brook Electronics, I had developed an image of Jack as something of a hi-fi purist. He certainly had the skills, experience, and resume to pass himself off as an electronics whiz-kid or an audio snob. I think it is still important to recall that Jack could have made ultra-clean, crazily-sophisticated amps if he had so chosen. However, he was evidently striving for something else -- a musical sound that was satisfying to his own ears and those of the musicians whom he consulted, not just to an oscilloscope. I readily admit that the aesthetic experience of electronically-produced sound waves is subjective and almost ineffable. However, as I struggle to find value in growing as old as I am, I can posit that standing in front of amplifiers for over 40 years has given me an opportunity to familiarize myself fairly well with how amps made by all the well-known manufacturers sound. Whether one likes the Hilgen sound or not, I am convinced that it is unique, and that Jack imagined a sound that no one else thought could be captured. Do you want to play a solid body electric and still hear the harmonics that vibrate from an acoustic guitar? If so, get a Hilgen amp.

Despite the quality of the Hilgen amplifiers, sales were evidently disappointing. In 1967 Mr. Silva decided to dissolve the partnership and liquidate the business. He took possession of all Hilgen stock and work-in-progress.

After Hilgen closed its doors, Jack began a new company, "Applied Audio," which for a few years made transistorized amplifiers and effects for the Guild company. Applied Audio was based in Manville, New Jersey. Reputedly Jack found the sound of transistorized amps distinctly inferior to those of tube amps.

In the end, Jack quit the electronics business and became a successful real estate investor and appraiser. He died on May 15, 2000 in Toms River, New Jersey at the age of 80.

Sadly, Jack appears to have regarded his career as an amp designer and builder to have been a failure. He died never dreaming that, within a few years, musicians throughout the United States who were searching for an alternative to the overdone Fender/Marshall sound would discover his amplifiers and marvel at their tone, style, and articulation..

You're going down in history, Jack. It's about time.

Hilgen's first amplifier was the "HM-B." Not much of a name. Perhaps that's why "HM-B" only appears in tiny little letters on the right side of the control panel. In the middle, where the model name would ordinarily appear, are printed the words "High Quality Amplifier." Hmmm. Where have we heard that before? There was no indication whether it was a guitar amp, a bass amp, or an accordion amp, although it had separately labelled inputs for each of them. The schematic for the HM-B (the only Hilgen schematic known to exist) describes it as a bass amplifier. But all the consumer evidently needed to know was that it was a "High Quality" amplifier -- just like Brook, and just like Sano.

Mr. Silva recalls that Jack continued the Sano tradition of attempting to make Hilgen amplifiers suitable for accordion. Mr. Silva unsuccessfully urged Jack to develop an amplifier specifically designed to amplify the electric violin. I thought that a rather odd statement until I discovered that Fender had made an electric violin in 1958-1959 and that both Rickenbacker and National had produced electric violins in the 1930's and 40's. Where would be now if Hendrix had picked up the electric violin?

Hilgen remained a going concern from 1964 until some time in 1967. There are no records of how many amplifiers the company built or shipped. (Indeed, there is literally no documentary evidence of what went on at Hilgen -- including, most regrettably, schematics for any amplifier other than the early HM-B.) Jack often invited musicians to try out his new amp designs and provide feedback on how they could be improved before they were put into general production.

One of the most telling descriptions I have heard of Jack is the following: "He was not so much an audiophile but fascinated with what he could do with sound." At first I was taken aback my that observation; because of his early involvement with the upscale Brook Electronics, I had developed an image of Jack as something of a hi-fi purist. He certainly had the skills, experience, and resume to pass himself off as an electronics whiz-kid or an audio snob. I think it is still important to recall that Jack could have made ultra-clean, crazily-sophisticated amps if he had so chosen. However, he was evidently striving for something else -- a musical sound that was satisfying to his own ears and those of the musicians whom he consulted, not just to an oscilloscope. I readily admit that the aesthetic experience of electronically-produced sound waves is subjective and almost ineffable. However, as I struggle to find value in growing as old as I am, I can posit that standing in front of amplifiers for over 40 years has given me an opportunity to familiarize myself fairly well with how amps made by all the well-known manufacturers sound. Whether one likes the Hilgen sound or not, I am convinced that it is unique, and that Jack imagined a sound that no one else thought could be captured. Do you want to play a solid body electric and still hear the harmonics that vibrate from an acoustic guitar? If so, get a Hilgen amp.

Despite the quality of the Hilgen amplifiers, sales were evidently disappointing. In 1967 Mr. Silva decided to dissolve the partnership and liquidate the business. He took possession of all Hilgen stock and work-in-progress.

After Hilgen closed its doors, Jack began a new company, "Applied Audio," which for a few years made transistorized amplifiers and effects for the Guild company. Applied Audio was based in Manville, New Jersey. Reputedly Jack found the sound of transistorized amps distinctly inferior to those of tube amps.

In the end, Jack quit the electronics business and became a successful real estate investor and appraiser. He died on May 15, 2000 in Toms River, New Jersey at the age of 80.

Sadly, Jack appears to have regarded his career as an amp designer and builder to have been a failure. He died never dreaming that, within a few years, musicians throughout the United States who were searching for an alternative to the overdone Fender/Marshall sound would discover his amplifiers and marvel at their tone, style, and articulation..

You're going down in history, Jack. It's about time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

You would not be viewing this website had it not been for the assistance of two individuals who did not know me from Adam but who gave selflessly of their time in solving The Mystery of the Lost Hilgen Company: Miriam Bein, Director of the Hillside Public Library in Hillside, N.J., and Dale Spindel, Director of the Kenilworth Public Library in Kenilworth N.J. I had never even thought to contact a research librarian before; I imagined them to be irritable old men or women, hunched over stacks of mouldering papers, making a half-hearted effort to locate what they considered to be useless information. Miriam and Dale might as well have been twin avatars of Sherlock Holmes: forming hypotheses, following clues, cursing false leads, reveling in the hunches that paid off. They were delightful, resourceful allies -- the best friends a rock'n'roll historian could possibly have. Thanks again, Dale and Miriam!

RESEARCH LIBRARIANS RULE

You would not be viewing this website had it not been for the assistance of two individuals who did not know me from Adam but who gave selflessly of their time in solving The Mystery of the Lost Hilgen Company: Miriam Bein, Director of the Hillside Public Library in Hillside, N.J., and Dale Spindel, Director of the Kenilworth Public Library in Kenilworth N.J. I had never even thought to contact a research librarian before; I imagined them to be irritable old men or women, hunched over stacks of mouldering papers, making a half-hearted effort to locate what they considered to be useless information. Miriam and Dale might as well have been twin avatars of Sherlock Holmes: forming hypotheses, following clues, cursing false leads, reveling in the hunches that paid off. They were delightful, resourceful allies -- the best friends a rock'n'roll historian could possibly have. Thanks again, Dale and Miriam!

RESEARCH LIBRARIANS RULE